Iteration 11

29 March - 8 May 2021

Kiriana O’connell + Eleanor Cooper + Faith Wilson

We are pleased to launch our writers thread into the project. Thank you to Kelly Carmichael, author of the introduction text to the ‘Iteration 10, Portraits’ publication, for inviting Faith Wilson into this special iteration. The text is installed into the gallery space on a monitor with scrolling text to audio application. We enjoyed teaching the text bot to kōrero i te reo Māori!

My dreams told me to wait, your time is coming

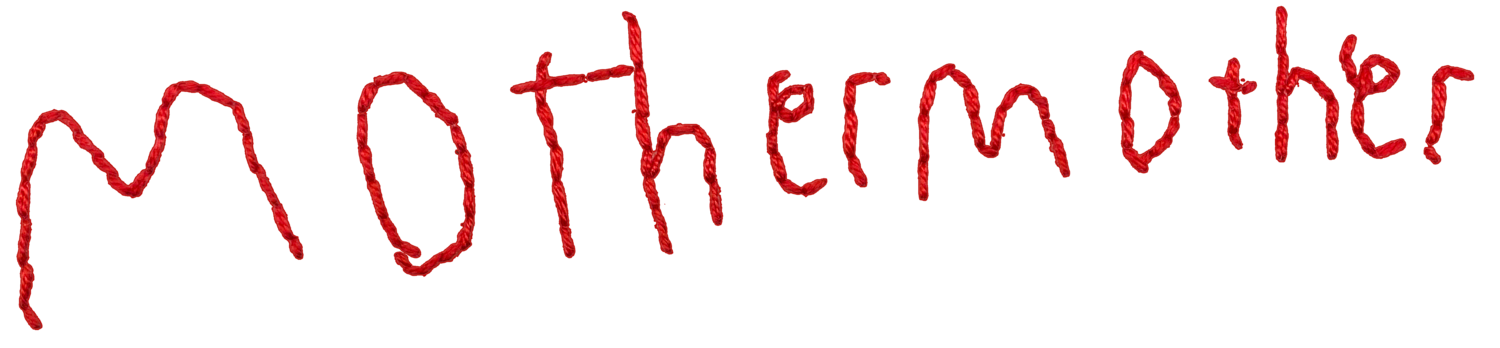

Response to Kiriana and Eleanor’s installation for mothermother, by Faith Wilson.

I had a dream once, years ago, that I still remember vividly. I am standing in the middle of a river, and I am staring at the face of a young boy. The air is hazy and ethereal, a heavy mist, the kind that you can only find floating on top of a body of water. The boy has dark brown skin, and dark brown eyes, and dark brown hair. We are standing in the water. We don’t speak. There is a shared knowledge or understanding. A kind of peace, or maybe a potency. I’m staring at him and then I hear an echo in my head. It’s loud, and surrounds us. It’s a voice, but it doesn’t seem to come from a person or a body. It just is. I think the boy is communicating to me in my head, without words. Like telepathy I suppose. He stares at me and I hear the word ‘papoose, papoose’. And then I wake up.

It’s a Sunday afternoon and I’ve rushed to the gallery to meet Nat, Kiriana and Eleanor. I’m late, but it’s okay because it’s Sunday and I’m in Tāmaki and time is a construct. Lol.

This is my first time meeting them in the flesh. We met online a couple of weeks ago and we let the conversation wander, snaking its way around us and through us and finding its own legs, threading together what could just be coincidence, but what feels like strange and strong connections between us.

One of the first things we do is eat a meal together. Even though it’s the first time many of us are meeting each other, it feels chill and I think it’s the comfort of knowing we’re in a safe place. We’re all women coming together without pretence and we’re drinking warm beer and talking with our mouths full and Eleanor has a broken arm so we take turns serving her up food and she is thankful.

Nat’s son is in the gallery space playing video games. I think about the gallery’s name mothermother and that we carry within us as humans, mostly, the potential for life. We’re vessels with many other purposes yes, but we’re vessels, bodies that hold pasts and futures and generations within us. Eyes, hearts and teeth. Life.

Papoose

Installation view

Eleanor Cooper

Installation view

Eleanor Cooper, detail

Eleanor Cooper

Installation view

Kiriana O'connell

Eleanor Cooper

On our Zoom chat Kiriana, a weaver, talked about weaving wahakura for a charity in Tāmaki, sleeping bassinets for pepe. I think about my dream and I Google what papoose means, because it’s not a word I can ever remember using.

A papoose is an outdated term that can be used as a potentially offensive or stereotypical word for an Indigenous American child, but it is actually a Narragansett word for a baby carrier. Maybe I heard this word in a TV show or read it in a book when I was young and now my adult self is wanting me to remember something. I think about what it means to carry a baby, to create space for a small human. mothermother, the name of Nat’s project and gallery space. Mother, a role you play. A role you become, maybe.

I don’t have a pepe, but I want to bring a life into this world.

Pepe

Pepe means baby in Sāmoan, but it also means butterfly. A baby is a new offering to the world; a butterfly on the cusp of death.

I think always about the actions that led us to this point in time, and while I don’t believe in fate, I believe in something deeper, and more profound, the strings of time pulling always in multiple directions, from multiple dimensions and pasts and presents and futures.

Eleanor broke her arm skateboarding and so instead of making new work, she’s installing some art she made previously, The intriguing lifecycles of the pūriri moth, Chinese tree privet, tree wētā and bracket fungus.

With this installation, a rope hangs diagonally across part of the gallery, from one corner to about a third of the way across the room on the other side. Hung over this rope are other kinds of ropes of sundry lengths and sundry colours.

As we’re eating, Nat walks over and points different ropes out to me as Eleanor tells the story of the privet tree, and the pūriri moth, or pepetuna, and how it stays in the caterpillar stage for up to six years in the trunk of the privet. When it finally metamorphoses into a moth, it’s alive for only a couple of days, born only to reproduce, born without a mouth for it has no need to eat, born to make life and then to return to the earth. Energy. Dust. Wētā shells.

Eleanor’s rope lengths and colours correspond to these different stages, and she says it’s a different way of thinking about time. She talks about wētā and fungus too but I can’t remember what she said because I was too enraptured by the story of the moth.

I tell Eleanor I wrote a book of poetry called Pepe, based on the life cycle of a butterfly but that the book feels stuck in stasis, unready to go into the world.

I don’t tell her the frustration I’ve felt at myself for failing continually to produce anything I deem worthy enough to be published. How I feel constantly like a failed artist, and the bar I’ve set myself for success is at odds with who I am as a person.

I talk about the constant contradictions of wanting the glow of the light, and conversely craving the comfort of the dark alone space.

After I talk to Eleanor I consider that maybe the caterpillar stage is just as, if not more important than the butterfly/moth stage. Maybe the book’s time as a caterpillar has not yet ended, and it’s not ready to be a pepe.

Pango/uliuli/black

Kiriana is obsessed with the colour black at the moment. Her big woven piece on the wall, Te Rauaroha hanging opposite Eleanor’s ropes, is like an abstract painting. Its thick, black weave and weft, with lighter coloured patterns woven through it.

The angles and precision in her piece are in contrast to the haphazard loops of Eleanor’s ropes.

Kiriana says that the colour black has so much meaning in Māori mythology. Te kore. Te pō. Prestate and then darkness.

Black is too, of course, the colour of death in many cultures. What comes after death? We live these fragile lives afraid.

I think of Eleanor’s pūriri moth. Prestate. Darkness. What comes after death? Blackness. Death. Rebirth? Maybe we’re all just caterpillars.

I think of the Vā, a potent space that as much as I try I can’t wrap my head around fully, just touching it sides every now and then. I think dreams come from the Vā space, where knowledge subsists and wends its way into your subconscious when you need to know something. Past selves talking to present selves. Ancestors immanence. It’s always there, ever-present.

As we sit there together, eating, talking, drinking, sharing space, I am wondering what I will write about, what threads I will eventually draw together to make something cohesive to present to the world, or at least a very small part of it.

It’s all significant, every weft and weave of Kiriana’s kete kupenga Te Kurawaka, and the bright red dyed flax that Kiriana says a big black lump of obsidian will sit in the middle of. Red, the colour of blood, that flows freely, glowing.

Tuna

I dream of eels constantly. Swimming and writing in the front yard of my parents’ house one night. Swimming and writhing in their backyard the next. What messages is the Vā sending to me? I can’t decipher, but I let it sit with me. My mum says it's to do with navigation and where I’m at in my life. I don’t disagree. In my dream I feed the eels big chunks of bloody flesh. They are hungry.

So much effort goes into the making of an artwork. The harvesting of the materials. The dyeing of the rope or the harakeke. The making of it. The thinking alone, of concepts, of symbols. The narrative.

I go back to Pepe, my poetry book that is still sitting in my Google Drive, untouched for at least two years. I feel guilty about neglecting it.

Return to the pūriri moth, to the pepetuna, and think about this exhibition, a mere glimpse really, a snapshot in time that although, yes, is significant, is not all that these works are made for. It doesn’t account for the hours spent weaving, the time spent dyeing ropes and researching privet and the emotion and the labour and the process and the counsel. Yes, as Kiriana says, weaving calms her, bringing her to a state of mauri tau, a state of ease, or a meditative fugue.

Maybe I am learning to appreciate the making more, the harvesting of the flax.

Just like this piece of writing is an accumulation of threads, it’s not all the threads and it’s not all that I am. It’s an offering that will be read by some, maybe many but probably less. It’s my story though. And it is not confined to any predestiny. Unlike the moth, I can give my words a mouth. Here it is, open wide. A mouth that speaks from the depths of my soul, reaching far into the Vā space, out into my dreams.

I return to my dream. Papoose. I stare at the boy and his eyes are familiar, eyes that I have known since before I was born, eyes that stare into the future. Papoose. Wahakura. Kete Kupenga. Womb. A thing to hold something. A blank sheet to hold a story. A tree trunk to hold a caterpillar. A kete to hold a thing you value. A body to hold a throbbing heart.

Papoose. Your eyes are mine. Pepe. My butterfly. My promise of life.