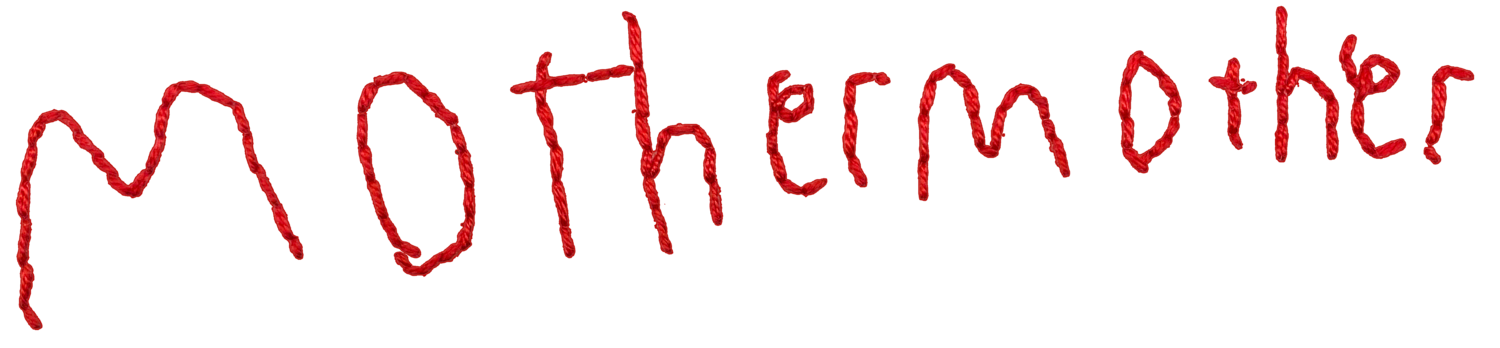

get a grip

Robyn Walton

26th June - 21st July 2023

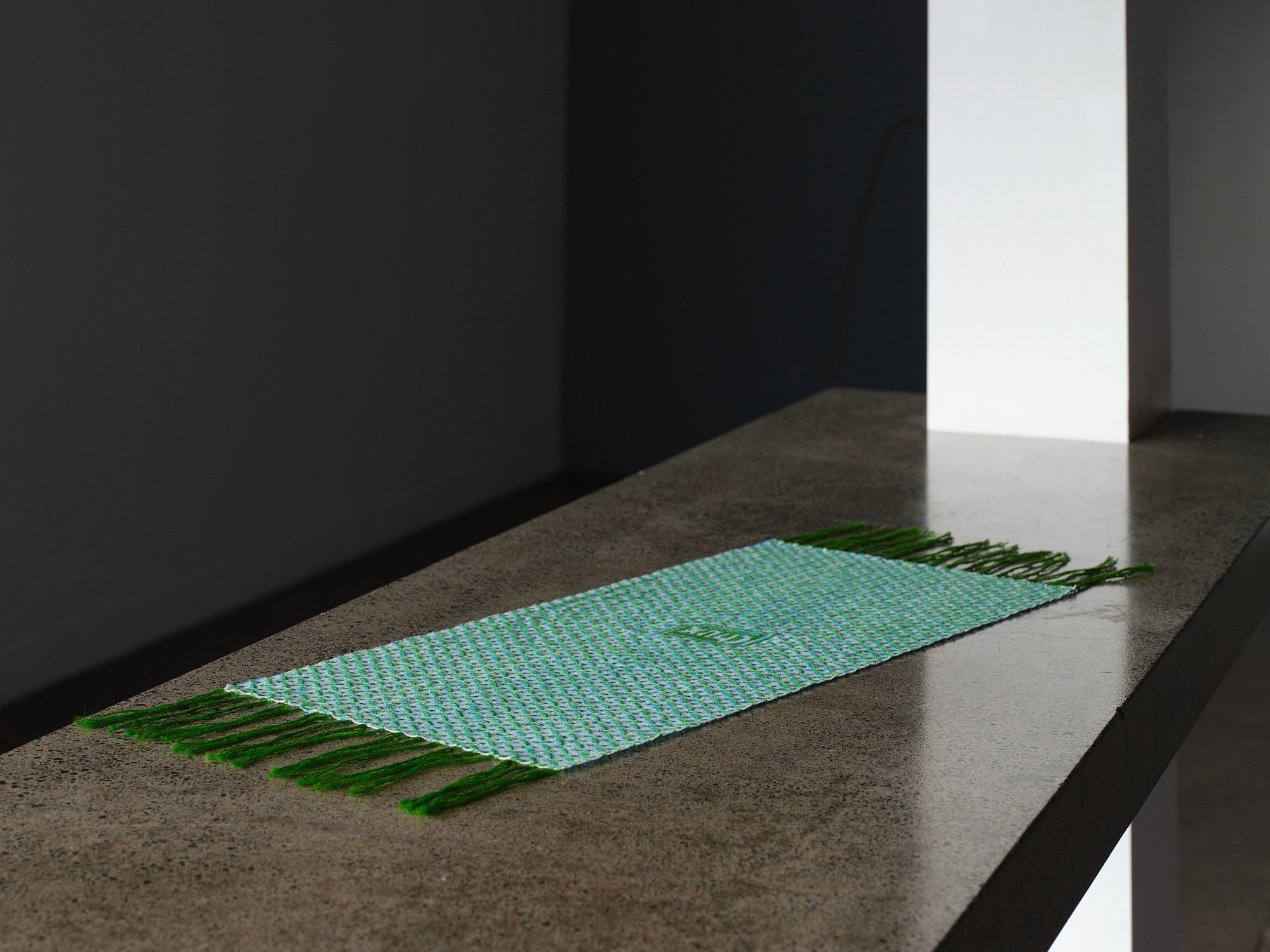

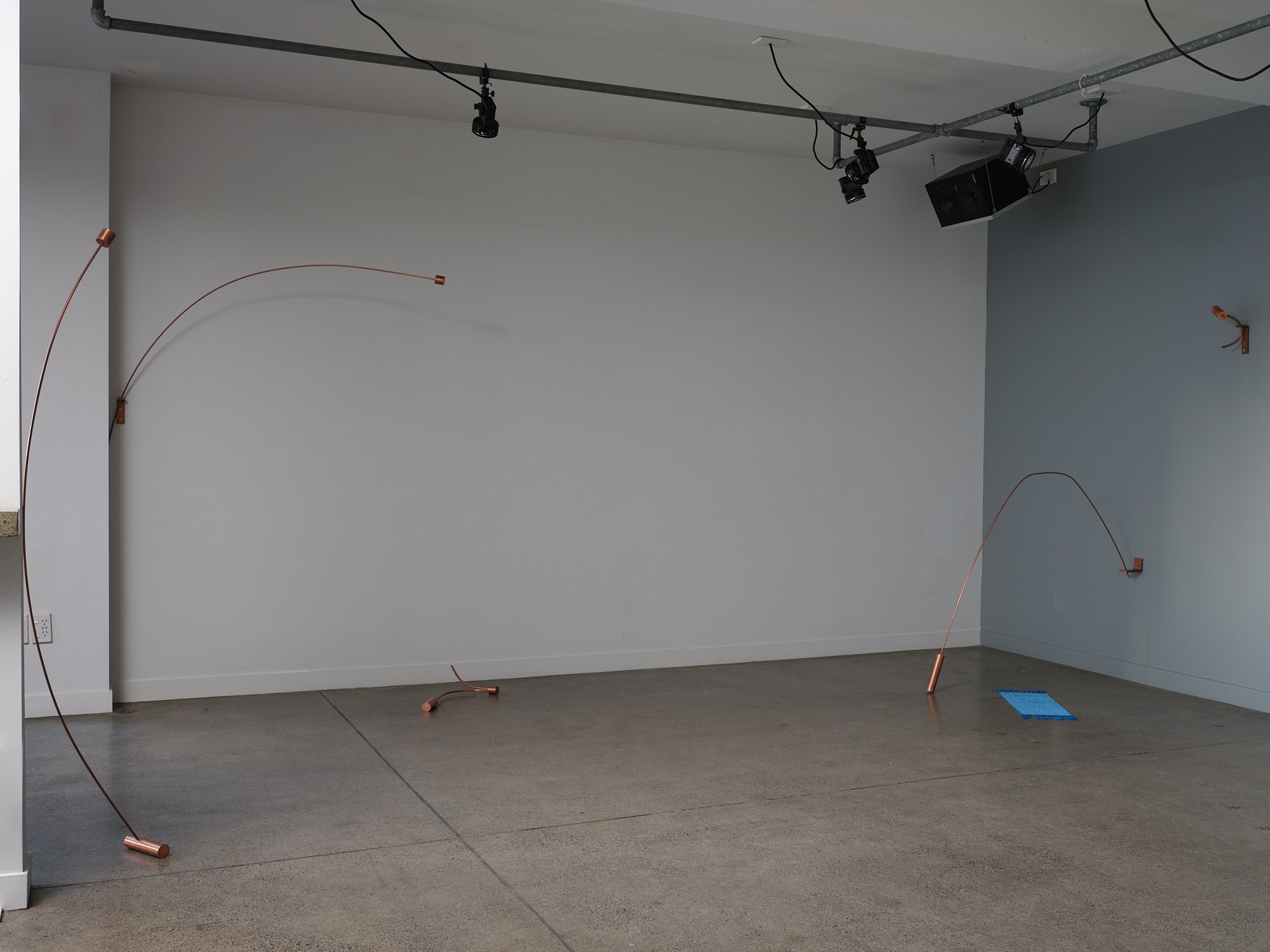

get a grip is a family of sculptural elements which speak to functional equipment. Formally inspired by domestic hardware, cloth and copper objects are familiar and purposeful yet oddly redundant.

Fixtures we handle hold a special place in our perception of domestic space. Copper has antimicrobial properties that interact with proteins to inhibit sperm, bacteria and viruses, killing SARS-Cov-2 in one hour appeasing even the most anxious. Each touch of a hand registers a trace on its surface. To accept this patina of use is to refuse reproductive labour.

Obscured or ambiguous purposiveness provides the primary line of enquiry. Walton appropriates mundane material as part of an ongoing concern with the theme of utility – particularly in relation to reproductive labour and maintenance work. Subverting the function of everyday objects upends our understanding of what an art object or a utilitarian object could be. This instability is readily apparent when something is used in an unauthorised way – and becomes the prompt for a different kind of attention. As purpose is confounded associations are expanded beyond the zone of household activity.

Misuse Value

An excerpt from On the Useful Object and its Objection to Being Used by Robyn Walton

“Once the commodity had freed objects of use from the slavery of being useful, the borderline that separated them from works of art … became extremely tenuous” (Agamben 42).

There are those who argue that to be useful and to be beautiful are two mutually exclusive states of being. In his Critique of Aesthetic Judgement, Immanuel Kant claims that any notion of pure aesthetic judgement expressly excludes utility. With regards to an object’s utility (or extrinsic objective purposiveness) our interest in the intended purpose of the object is the basis for any liking. We are aware of its causal concept and are appreciative if, in use, it meets those requirements well.

Intrinsic objective purposiveness, or inner purpose, is instead derived from an object’s perfection. We perceive it as the product of some will, or concept (what sort of thing is it meant to be), and our judgement of its perfection is based on “the harmony of the thing’s manifold with this concept” (74). For Kant this notion of the perfect, or good, is closer to the ideal of beauty, although beauty must be a liking for the thing itself without reference to any concept: “The beautiful, which we judge on the basis of a merely formal purposiveness, i.e., a purposiveness without a purpose, is quite independent of the concept of the good. For the good presupposes an objective purposiveness” (73).

Kant allows a certain ambiguity into his system in the form of exemptions for obscurity or lack of knowledge (78). A pure judgement of taste may yet be made, if a useful object is abstracted from its purpose, or if the person judging it has no concept of its purpose. His classic example of beauty (formal purposiveness without reference to purpose) is the flower. This is problematic however, as the flower obviously has a very defined purpose (to enable reproduction) which determines its form. However, Kant claims that when “we are judging the flower, we do not refer to any purpose whatever” (84 emphasis added). It goes both ways: there are some beautiful things which turn out to have purpose (flower) and “…there are things in which we see a purposive form without recognizing a purpose in them (but which we nevertheless do not consider beautiful)” (84).

The most interesting aspects of Kant’s Critique are these grey areas. He raises a set of possible questions for analysing the success or failure of objects with ambiguous or frustrated purpose. How do viewers respond to these objects? Can the sense that there is some unknown purpose or perverted utility provoke some sense of unease? How is objective purposiveness judged if it is unclear what that intended purpose is? Is it possible to intentionally muddy the waters of purpose to mine the discomfort of the ‘wrong’?

According to the philosopher Jean Baudrillard every object has two functions; to be put to use or to be possessed. “A utensil is never possessed, because a utensil refers one to the world; what is possessed is always an object abstracted from its function and thus brought into relationship with the subject...” (Marginal System 86). Every object oscillates between the two categories, as Baudrillard makes clear: “Our ordinary environment is always ambiguous: functionality is forever collapsing into subjectivity, and possession is continually getting entangled with utility, as part of the ever-disappointed effort to achieve a total integration” (Marginal System 86-7).

Utility and possession, Baudrillard’s two categories of object function, are rooted in Karl Marx’s theory of use value and exchange value. The Marxian commodity is either produced to satisfy a need (subsistence), or to exchange for money (capitalism) – in which case the required labour power (and potential use value) can be obscured. With the commodity fetish a symbolic value of desire is overlaid onto an object’s normal use.

The branded commodity transforms this symbolic value into real exchange value, servicing a kind of lifestyle totemism – “commodities as carriers of social values” (Simon 33). Aspiration can dictate an exchange value out of all proportion to either the true production cost of an object or its use value. This immaterial value of the commodity fetish emerges from seemingly nothing. In actuality we are all responsible for creating the value of commodities that we aspire to. We have power. As the symbolic capital of conspicuous consumption, these products have no natural divine desirability, they are valued precisely because we desire them, and we are manipulated into desiring them. Some power may be reclaimed by looking beyond the commodity fetish to see use value, to see the productive labour which has been concealed behind image and desire.

For Baudrillard, once stripped of utility, “the pure object, devoid of any function or completely abstracted from its use, takes on a strictly subjective status: it becomes part of a collection… An object no longer specified by its function is defined by the subject” (Marginal System 86). In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin defines a collector as one who detaches the object from its original context or function, in order to bring it into a close relationship with others of similar typology (204). The act of organisation endows the collected objects with an abstractness, by which Baudrillard suggests “the everyday prose of objects is transformed into poetry” (Marginal System 87).

Jac Leirner’s Hardware Silk is such a case in point. A “plethora of holed or hollow pieces of hardware” have been collectively penetrated by a taut steel cable, suspended just below eye level (Martins 227). The paraphernalia of art installation, normally tidied away before the exhibition opens, is instead laid out for our close inspection. “The ‘sex appeal of the inorganic’, strangely inscribed in the commodity-object, rises to the surface only when contemplation strips it of its proper contexts” (Müller 88). Leirner’s work highlights the rich variety of colour, texture and form present in the group of objects, linked (literally) by the fact that they share the common attribute of a round hole.

Local artist Chris Braddock collects certain kitchen ephemera (among other things). Whisks and sink strainers gathered in their respective large groupings emphasise small differences rather than similarities. That they are similar seemingly goes without saying. Braddock does not claim these as artworks, but they are more than utensils – they have traversed into the grey area. The fungible object has fallen into a new life as possessed object, which takes part in a direct relationship with the subject-viewer. The objects have been denied their function, or rather they have been assigned a new purpose as a thing. Critical theorist Bill Brown refers to this notion as misuse value – the dislocation from habitualised objectification allows for an appreciation of the object-being itself (Other Things 51).

“The story of objects asserting themselves as things, then, is the story of a changed relation to the human subject and thus the story of how the thing really names less an object than a particular subject-object relation” (Brown Thing Theory 4).

According to Martin Heidegger, “the mere thing is a kind of equipment that has been denuded of its equipmental being” (11), it has lost the qualities of serviceability and of being made. Heidegger’s equipment is an object in the world that we make use of in order to achieve some ends – a tool if you will. But, as soon as the object no longer serves, it reverts to being a thing. For Heidegger therefore, equipment occupies a strange no-man’s land between thing and work of art, with something of the nature of each. It is like the artwork in that it is man-made, it is unlike the artwork in that it does not have the quality of self-sufficiency, of having perhaps taken shape of its own volition.

“A piece of equipment, for example, the shoe-equipment, when finished, rests in itself like the mere thing. Unlike the granite block, however, it lacks the character of having taken shape by itself. On the other hand, it displays an affinity with the artwork in that it is something brought forth by the human hand. The artwork, however, through its self-sufficient presence, resembles, rather, the mere thing which has taken shape by itself and is never forced into being. Nonetheless, we do not count such works as mere things. The nearest and authentic things are always the things of use that are all around us. So the piece of equipment is half thing since it is characterized by thingliness. Yet it is more, since, at the same time, it is half artwork. On the other hand, it is less, since it lacks the self-sufficiency of the artwork. Equipment occupies a curious position intermediate between thing and work- if we may be permitted such a calculated ordering” (Heidegger 10).

Elsewhere Heidegger argues the artistic nature of artwork lies in its allegorical role: its ability to manifest something other than its own thingness (3). In this it anticipates the branded commodity as a carrier of sign value. The immaterial labour of the avant-garde readymade did not merely mime and mock “the degraded world of capitalist modernity” as Foster would have it (15-16). Rather the surrealists prefigured the impending explosion of assigned value of the branded commodity-fetish-worship of the contemporary world of neoliberalism.

“Breton quoted Hegel to the effect that the art object lies ‘between the sensible and the rational. It is something spiritual that appears as material.’ Thus Breton anticipated the rhetoric of contemporary capitalism, according to which commodities are almost accidental materializations of a transcendent brand identity” (Lütticken 111).

Much earlier, in 1855, Charles Baudelaire experienced the great concentration of commodity objects that was the Paris Universal Exposition. The spectacle attracted crowds who marvelled over novel products as if they were artworks. This enabled Baudelaire to ascertain that the aura surrounding the work of art is “the equivalent of the fetishistic character that the exchange value impresses on the commodity” (Agamben 42). Fetishization is taken to its extreme where it becomes the entire use value of the (art) object. For Baudelaire, art is the new absolute commodity:

“…a commodity in which the form of value would be totally identified with the use-value: an absolute commodity, so to speak, in which the process of fetishization would be pushed to the point of annihilating the reality of the commodity itself as such. A commodity in which use-value and exchange value reciprocally cancel out each other, whose value therefore consists in its uselessness and whose use in its intangibility, is no longer a commodity: the absolute commodification of the work of art is also the most radical abolition of the commodity” (Agamben 42).

Curator Joshua Simon argues that the art exhibition allows us to see commodities clearly for what they are: “More than in any other context, commodities are most true to themselves as art” (38). In his book Neomaterialism, Simon suggests that the base material for all art practice is now the commodity itself. Everything around us “in our prefabricated world” is the commodity – we merely refashion it into art which references that world (38). The objects are used as collaborators: “…the attempt to apply any authority over things, to own them, is a failed task” (15).

Simon has coined the term unreadymade in reference to such assemblages, which aim to undo “the process of authorship through appropriation” (45). “While the readymade uses display to make things from the world become art, the unreadymade uses display to make what is shown as art testify to its existence in the world as a commodity” (41). For Simon the exhibition is an opportunity for contemplation of the new post-appropriation assemblage as the commodities re-emerge into the material world.

Which raises the question of what happens to the objects post-art? If the component parts of the artist’s assemblage have been created by the material labour of others, and merely selected and positioned by the artist, what happens after the show? Does it all return to being regular stuff, or, like some kind of ‘as seen on TV’ prop, does it have proximity value? Does it have the added desire value, or mystique, of the artist’s immaterial labour? In short, does creating a new thought for an object create a new value?

Artist Luke Willis Thompson has explored this territory with in this hole on this island where I am, 2012. His readymade, although remaining in-situ, was displayed within an art context by virtue of being accessed via the dealer gallery Hopkinson Cundy. The entire family home – complete with contents – was available as an artwork, price on application (Thompson). During exhibition hours the occupants were unable to use the house-as-house, which became house-as-art-object.

Thompson juggles art object with sentimental, use and property-market exchange value in a ‘mare’s nest’ of identity. The very definition of Simon’s unreadymade, Thompson’s house makes what is shown as art testify to its existence in the world as a commodity. All the mundane stuff of life is laid bare for the viewer in a strange parody of the staged open home. Everything is personal – sentimental value is readily apparent but inaccessible. We see everything but we know nothing – resembling Oscar Wilde’s cynic who “knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing” (38).

House-as-art-object was entirely dependent upon a choreographed taxi-ride from the gallery: “The house can be an artwork, or a house, depending on how it is approached” (Thompson) Which implies that it can exist as both house and artwork simultaneously. After the show, the house reverted to being an ordinary house, only to re-emerge as an artwork for the Walters Prize Exhibition in 2014. Things can be art, and then they can be “turned back on” to be ordinary things (Thompson).

In Attending to Abstract Things, art critic Sven Lütticken calls for utilising the “political aesthetics of things” as a site of challenge to contemporary capitalism, by developing a new kind of art: “Inverted ready-mades that are no longer content to create artistic surplus-value, but rather investigate the conditions for a different type of thing… If the surplus-value production of ready-made and surrealist objects anticipated branded capitalism, the question is what anticipations of a different economy might look like” (120). How can contemporary artists prefigure a future alternative to the current neoliberal environment? Lütticken suggests a reengagement with the material, by which he expressly does not mean some form of nostalgia for the primitive gift economy, but rather a kind of making real of the abstract. His proposal appears to have certain parallels with Simon’s unreadymade concept.

So, with the unreadymade, is the object taking some time out from its mundane commodity culture existence to experience life as pure form or art object? Or, alternatively, does functionality and utility instead represent time out for the fetishized commodity object – is it the art status which truly represents the ultimate in commodity culture? And what happens when the object apparently exists as both art and equipment at the same time?

In his book, The Tears of Things, Peter Schwenger discusses sculpture which incorporates actual pieces of equipment, stripped of their obviousness to allow thingness to emerge. Disconcertingly, aspects of these objects remain simultaneously recognisable as equipment: the ‘norm’ resurfaces within the uncanny version before us (70). Duchamp’s snow shovel, In Advance of a Broken Arm, 1915, is one such work. Presented hanging, a shadow cast upon the wall behind is a key aspect of the work, perhaps alluding to what Schwenger refers to as a double exposure:

“The viewer of Duchamp’s shovel, then, is not seeing it as pure art, with an appreciation of its clean lines and abstract appeal. Nor is the viewer seeing the shovel the same way in the gallery as would be the case if it were hanging in the garage. There is an uneasy flicker between two versions of worldhood, more disturbing than if either version prevailed” (54).

Gabriel Kuri’s art practice also incorporates ‘things from the world’. His sculptures operate as combinations or arrangements of unaltered commodities, in which the space and the relationships between the objects are just as significant as the ‘raw material’ itself, perhaps even more so. The possibilities and potentialities of combinations add a precariousness kinetic quality to what is an essentially stable composition – the potential for change. “Kuri’s found objects, often quite mundane, are transformed in his work to become like chess pieces which suggest a multitude of potential moves in all directions” (Wood 101). The objects utilised by Kuri appear to be merely passing by, occupying a temporary role as an artwork before returning to their former lives. Kuri’s 2007 work Vacio Olivia consists of two stacked cans of green olives securing a section of weatherproof roofing roll. Did anyone ever eat those olives? Or are the same cans kept in an archive somewhere along with a roll of unused roofing?

Similar questions arise regarding various readymades which were ‘lost’ only to reappear in the form of a new authorised edition. Was Marcel Duchamp’s original Fountain from 1917 actually installed as a urinal somewhere lost in the mists of time? And if not where did it go? Although impossible to ever verify, a Duchamp in the bathroom would be the ultimate Rembrandt in the attic moment. As well as the found object becoming an artwork, Duchamp himself also investigated the idea of artworks becoming mundane things. His inverted or reciprocal readymade concept suggested a Rembrandt being used as an ironing board. Duchamp’s interests appeared to lie with the nature of object-being itself.

Perhaps “use in its purest sense is the inverse of the commodity” as Chelsea College of Arts professor Neil Cummings has written. The utensil is not dictated by desire and aspiration. In a way indicative of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, western society no longer dreams of a bucket to make their lives complete. We exist beyond such physiological requirements; we now desire the brand that will bestow status in the eyes of our tribe. Utility is taken for granted. “Use could begin to operate as a brake, generate friction and slow the constant acceleration of a media saturated interpretation” (Cummings).

If this is the case, and use is a point of resistance to the seductions of the market economy, then surely misuse would be even more so? Unsanctioned use could operate as a subversive refusal of contemporary commodity culture. “It’s impossible to regulate for a useless corkscrew beautifully holding the door open” (Cummings). The re-purposing of the used, the retrieval of the discarded, the restoration or adaptation of the broken – all undermine the dictum of a consumer society that repair should be obsolete. By mending, fixing, re-using, and re-circulating, the bricoleur fights back from the brink of extinction. In his text “Reading Things: The Alibi of Use,” Cummings call for a re-engagement with the life-cycle of material things:

“The difficulty, no, the necessity, … is to try and see through the glittering, reflective sheen of the modern commodity. Perhaps if we begin to chart the object’s encounters in the babble of use, the natural resting place for invention and memory, we may encourage some resistance. Things here seem closer to their being, worn, expressive, stripped of hype and glamour, in the relative economies of use and need. This is where, I believe, an object’s real life begins…”

Works cited

Agamben, Giorgio. Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture. University of Minnesota, 1993.

Baudrillard, Jean. “A Marginal System: Collecting.” The System of Objects, New York, Verso, 1996, pp85-106.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Belknap Press, 1999.

Brown, Bill. Other Things. University of Chicago Press, 2015

--- “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry, Vol 28, No. 1, Things (Autumn 2001) pp1-22

Cummings, Neil. “Reading Things: The Alibi of Use.” (extract from the introduction to Reading Things, Sight Works. Vol.3, ed Neil Cummings. Chance Books London 1993.) Accessed via www.neilcummings.com/content/reading-things June 2017, unpaginated.

Foster, Hal. The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. MIT Press, 1996.

Heidegger, Martin. “The Origin of the Work of Art”. Off the Beaten Track, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp1-56.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Judgement. Hackett Publishing, 1987. Accessed 30 June 2018 via monoskop.org/images/7/77/Kant_Immanuel_Critique_of_Judgment_1987.pdf

Lütticken, Sven. “Attending to Abstract Things.” New Left Review #54, Nov Dec 2008, pp101-122.

Martins, Sergio. “Jac Leirner.” Art Forum, January 2013. pp227-8.

Müller, Vanessa. “Non-objective Objects: Some Remarks on Works by Thea Djordjadze.” Afterall, 1 April 2010, Issue 23. pp82-88. Accessed 30 June 2018 via www-jstor-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/20711783?seq=6#page_scan_tab_contents

Schwenger, Peter. The Tears of Things: Melancholy and Physical Objects. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Simon, Joshua. Neomaterialism. Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2013.

Thompson, Luke Willis. Lecture delivered September 2014. BFA Year 2, Elam School of Fine Arts.

Wilde, Oscar. Lady Windermere’s Fan. New York, Dover, 1998.

Wood, Catherine. “Sculpture, in Solid Air.” Soft Information in Your Hard Facts. Gabriel Kuri. Mousse, 2010, pp99-102.